Welcome back to A Journey into the Virtual World. In the previous post looked at a few more artists and inspirations for the project. If you missed that one, be sure to take a look back through the [VR]Ography section.

With the scene set, all that was left to do was get the footage saved. I did this using screen capture software, recording several versions of the piece, leaving the software running for an extended period in order to capture the scene to its fullest breadth, recording the shifting light and the changing weather. Once I had captured enough raw footage, it was time to work on editing and presenting, and although I had thought about creating a two-channel piece, I hadn’t yet considered exactly how that would look.

“While searching for a representation of truth, sometimes a manipulated image, sometimes a composite, something that is impossible to capture within the flattened rectangle of a photograph or a single lens may offer a closer experience to the one we’ve actually had.” – David Cotterrell.

Combining the real world and the digital 'other world’, for me, represented a journey in and of itself, and it was important for me to consider this when figuring out exactly how the work would be shown. As such, I decided that the two channels would be shown simultaneously, and possibly on the same screen, with the lift on the left, representing the descent as a means to another world, and the plane on the right, representing a means of travel to another world - each of a different world, one accessible by the other, at least visually, with the real us entering the lift to descend into the other ‘virtual’ world, a virtual world that represents a journey to a place of combative horror - a mover-day hell.

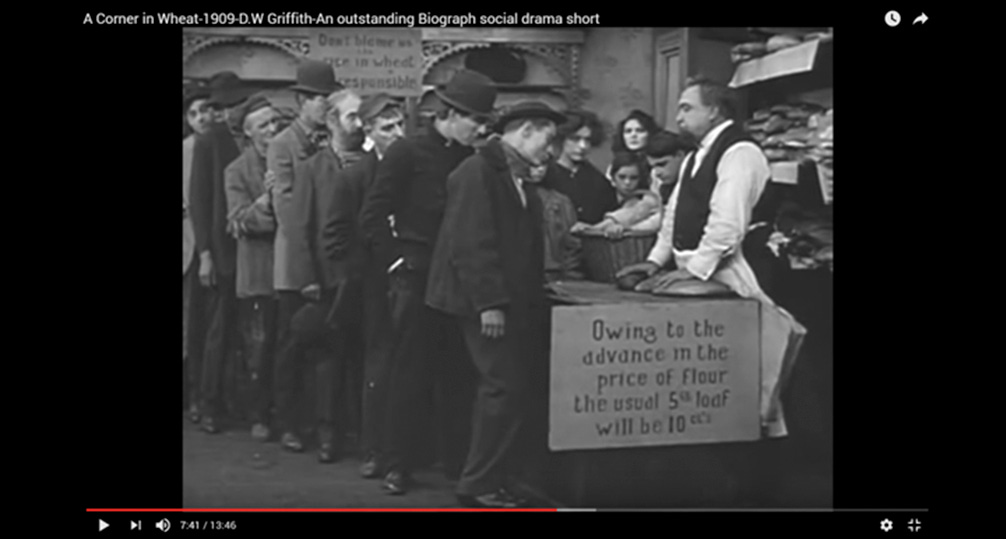

My inspiration behind my decision to display both clips at once came from precedents already set within the cinematic world. I initially considered cross-cutting, which is a technique is most often used in films to establish action occurring at the same time in two different locations. With cross-cutting, the camera cuts away from one scene of action to another, which can suggest the simultaneity of the two (although this isn’t always the case). A prime example of this is within the 1909 film ‘A Corner in Wheat’ by D.W. Griffith. In the film, we see a juxtaposition between the activities of the rich businessmen at a lavish meal and poor waiting in line for overpriced bread.

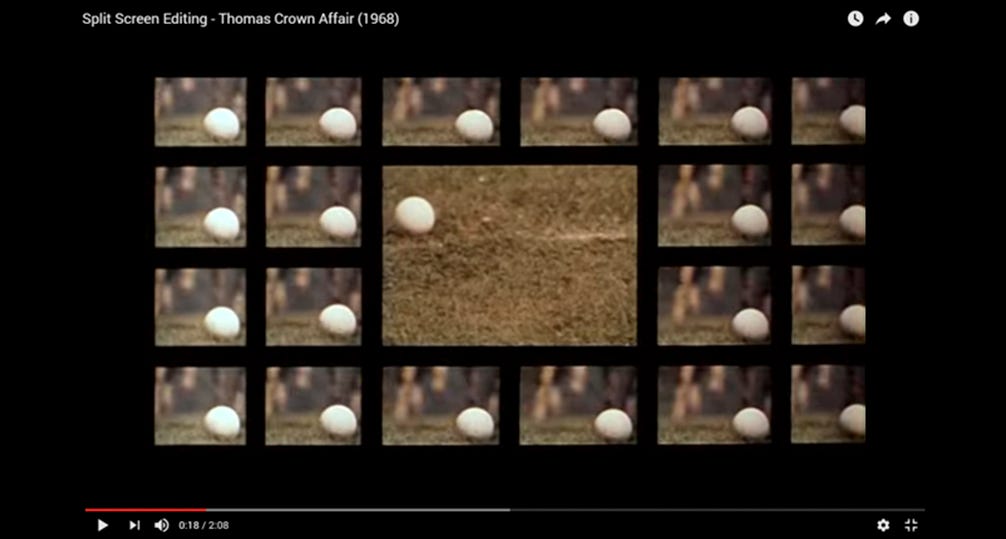

I discarded this technique however, opting instead for the split screen method. Within film and video production, split screen is the visible division of the screen, traditionally in half, but also often in several simultaneous images. This technique ruptures the illusion that the screen's frame is a seamless view of reality and is useful for conveying a sense of real-time action. An example of split screen in cinema is the 1967 film ‘A Place to Stand’ which was produced and edited by the Canadian artist and filmmaker Christopher Chapman. For the film, he pioneered the concept of moving panes of moving images within the confines of a single screen and at times, there are up to fifteen separate images moving at once. This technique, which he dubbed 'multi-dynamic image technique has since been employed in many films.

Other notable examples of this technique are in Norman Jewison's 1968 film ‘The Thomas Crown Affair’ as well as the 2002 television series ‘24’ created by Joel Surnow and Robert Cochran.

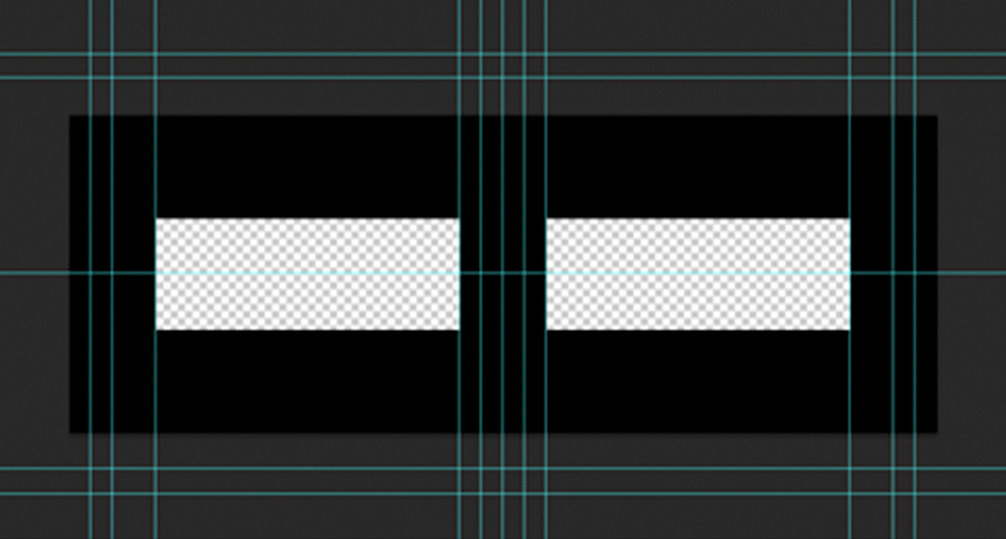

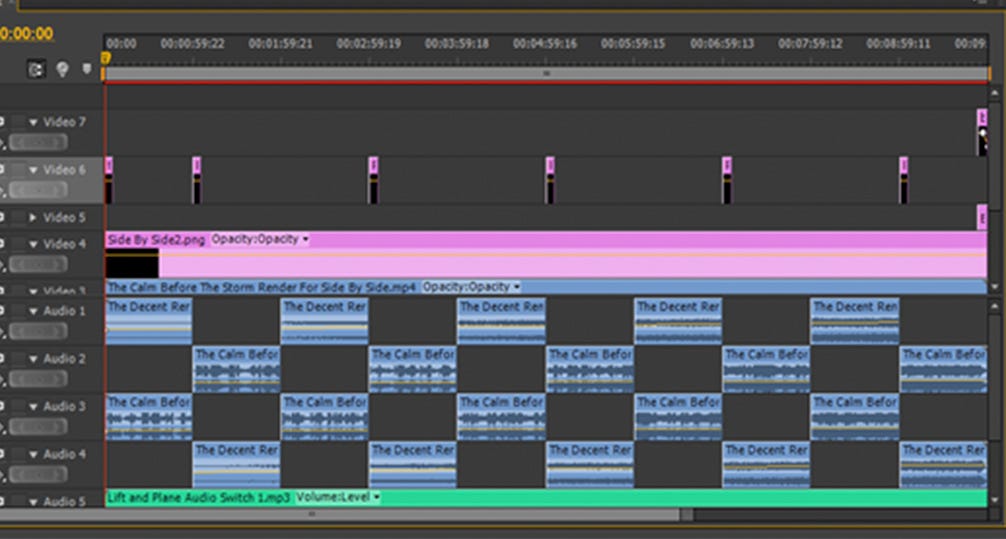

With these possibilities in mind, my first step in combining the feeds was the creation of a mask, which I made using Photoshop. This would allow me to properly place the footage within the screen without worrying about proportion errors. Once I had done this, I began a new project in Premiere Pro and after importing the mask, I brought in the footage and aligned on behind it, bringing the disparate works together for the first time.

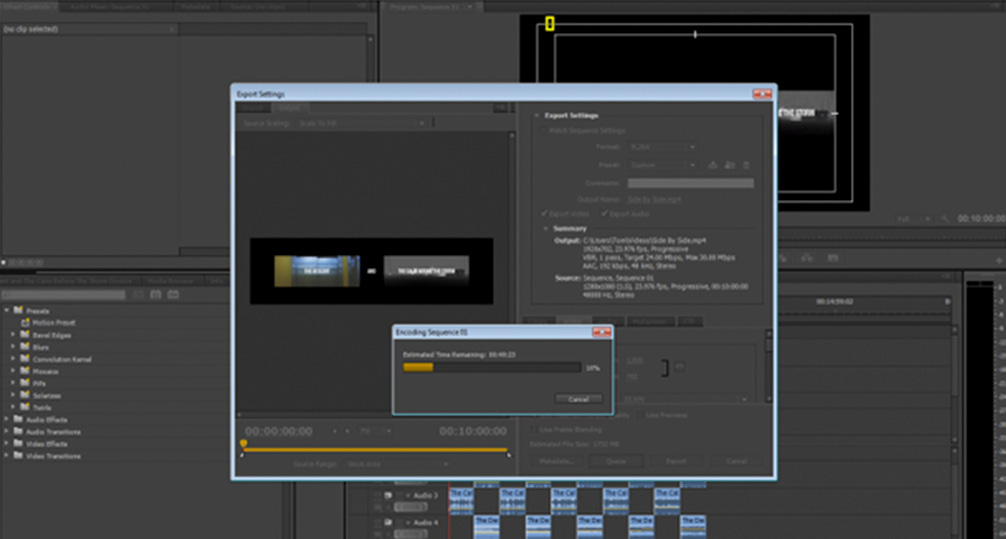

With the two clips sat side by side I rendered out the footage to get a feel for how the two pieces worked together, and whether they could convey the concepts brought up by the Orpheus myth which inspired the project - the lift representing Orpheus’ descent into the underworld and the airport representing Eurydice and her entrapment within the purgatory of the underworld. Visually I felt that the pieces accomplished this, and I was happy with the placement, but there were issued with the audio that needed to be resolved next.

The sounds of the lift and the atmospheric noises from the airport scene clashed somewhat when played back together, and I needed to find a way to play both tracks simultaneously without them interfering with each other or creating an auditory mess that would put off a viewer. I experimented then with panning the audio from the lift video to the left to match it’s positioning on screen, and the same to the airport audio, panning it to the right. This worked to some degree, but when listening back, both tracks seemed to lose too much depth and detail, so I experimented further by cutting the audio into ten one-minute-long segments and alternating them. I then overlaid the opposite audio tracks back in with a reduced volume. This was in reference to the cross-cut editing style but rather than used visually, I applied it to the audio. This still wasn’t quite to my tastes, so I decided to put the audio on hold while I continued my research and focusing again on the visuals.

In the next part I’ll be looking at incorporating text into the footage and experimenting with other forms of presentation before moving ahead with the video. If you want to read more on this project, check out the [VR]OGRAPHY section.

As always, thank you for reading. If you’d like to support the blog, you can do so by subscribing and sharing!

Also, a big thank you to the TYPEDBYTOM Patreon/BMAC supporter(s) this month:

Jamie B